Clouds and Light: Impressionism in Holland

Landscape painting originated in Holland, and the realism of the seventeenth-century Old Masters long set the standard. With the development of pleinair painting in France, nineteenth-century Dutch artists found new inspiration. The exhibition Clouds and Light: Impressionism in Holland showed from July 8 to October 22, 2023, how artists were inspired by French influences to create their very own Dutch form of Impressionism.

Ferdinand Hart Nibbrig: At the Dunes, Zandvoort, 1891-92, Singer Laren, gift of P. J. Hart Nibbrig 1981

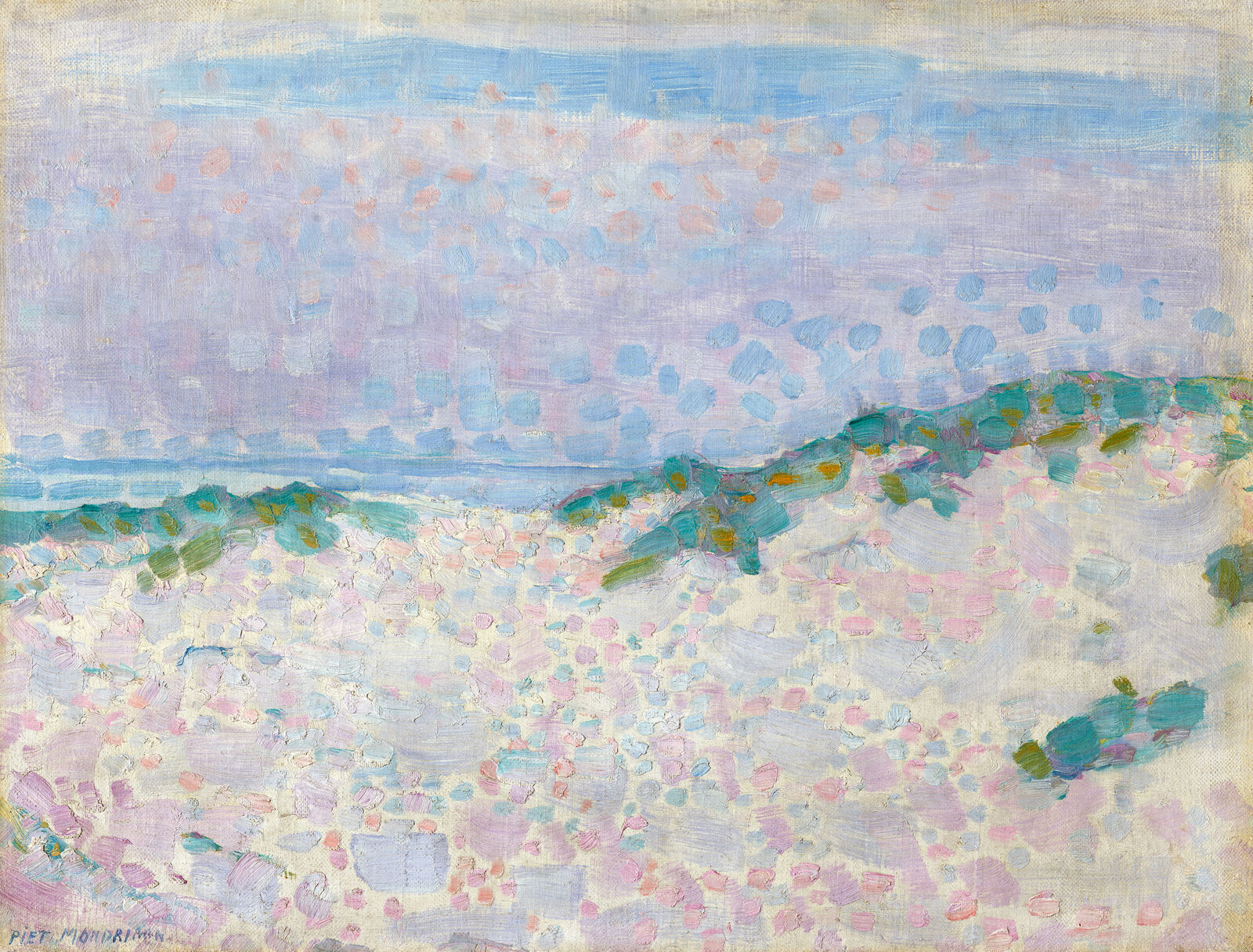

Piet Mondrian: Pointilistic Study with Dunes and Sea, 1909, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, Dauerleihgabe Privatsammlung

Painters of the Hague School captured nature’s changing moods of light in vast, cloudy skies using a wide range of grays. Beginning in the 1880s, Impressionist influences from France sparked an interest in cityscapes and images of modern life, followed by the unleashing of color in the painting of Pointillism.

When French artists of the 1830s began painting under the open sky in the forest of Fontainebleau and embraced momentary experience as a pictorial motif, they laid the foundation for the Impressionist movement. Only shortly thereafter in the late 1840s, painters in the Netherlands also began working en plein air, and they, too, sought out a natural, unspoiled forest for their experiments with light and shadow. They were soon exposed to the work of French artists from Fontainebleau, whether through visits to France or exhibitions in the Netherlands. Both the experience of nature in the forests of their homeland and the influences from France were informed by their own, Dutch tradition of seventeenth-century landscape painting.

The Dutch artists who went to the forest of Oosterbeek near Arnhem in the 1840s rejected Romantic or idealized images of the landscape and instead focused on the realistic depiction of nature. Painting under the open sky, they created studies of light and shadow, reflections on water, and the effects of backlight. Their works show unassuming motifs from nature and rarely include human figures, employing them only as accessories.

Around 1870, The Hague developed into a major center of the Dutch art world. The artists of the Hague School painted the nearby coast of the North Sea and the flat polder landscape typical of Holland with its meadows and cows, canals and windmills. The panorama-like scenes with low horizons and broad gray skies showed no action and ignored the changes of the modern era such as railroads or telegraph lines. The quiet, serene mood and subdued color of these landscapes were intended to evoke empathy and recognition. With their realism, these artists depicted a slice of the familiar world and at the same time reinforced notions of the unique character of their homeland.

While the painters of the Hague School stayed true to their motifs and painterly approach even into the 1890s and later, the following generation turned its attention to the city. The artists of the style known as Amsterdam Impressionism were open to modernity in terms of both technique and subject matter. Rapid brushstrokes and cropped compositions like those of the French Impressionists give the works a momentary, snapshot-like quality. The dynamism of urban life with all its facets became the primary focus. Boutiques, electric lights, and horse-drawn trams were the defining features of contemporary life. The seashore was of interest only as a place of leisure and entertainment: beach paintings focus on carefree holiday activities, with sky and ocean appearing only as narrow strips in the background.

While the Amsterdam Impressionists still used the muted, brownish-gray palette of the Hague School, the Pointillism of the 1890s introduced a hitherto unprecedented intensity of color into Dutch art. In this technique, developed in France, pictorial objects were constructed by means of meticulously juxtaposed dots of pure, unmixed color. For the Pointillists, the motif was less important than the visualization of light and color. The unleashing of color in the work of the French Fauves around 1905 was soon embraced by artists in the Netherlands as well. In the style known as Luminism, color was no longer employed for the naturalistic depiction of reality, nor was it associated with particular objects. Instead, it became an autonomous element and a means of expression. Effects of light and shadow continued to be of interest, but while forms such as houses, lighthouses, windmills, or trees remained recognizable, they were reimagined in brilliant, unmixed colors. The focus no longer lay on the representation of nature, but on the expression of the artist’s individual feeling. For many viewers of the time, this unprecedented break with the tradition of Realism was unsettling.

The Hague School and Amsterdam Impressionism had each introduced only one new style to Dutch art. After 1910, however, the avant-garde in Holland—as in other countries in Europe—branched out into multiple, simultaneously emerging directions. The rapid development of new formal languages also offered freedom in the choice of expressive means. Color and form now seemed more variable than ever before. Painters who had begun their artistic development around the turn of the century or later engaged in periods of experimentation with various processes. Cubist fragmentation, Expressionist exaggeration, or the dissolution of forms in abstraction removed the image of the landscape ever further from the rendering of the visible world.

Jacob Maris: Stone Mill, ca. 1890, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, acquired from Mr. E.H. Crone with support of the Rembrandt Association

George Hendrik Breitner: The Bridge over the Singel at the Paleisstraat, Amsterdam, 1898, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Mr. and Mrs. Drucker-Fraser Bequest, Montreux

The exhibition Clouds and Light: Impressionism in Holland brought together around a hundred works by some forty artists including Johan Barthold Jongkind, Vincent van Gogh, Jacoba van Heemskerck, and Piet Mondrian. Lenders included the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, the Dordrechts Museum, the Kröller Müller-Museum in Otterlo, and the Singer Museum in Laren.

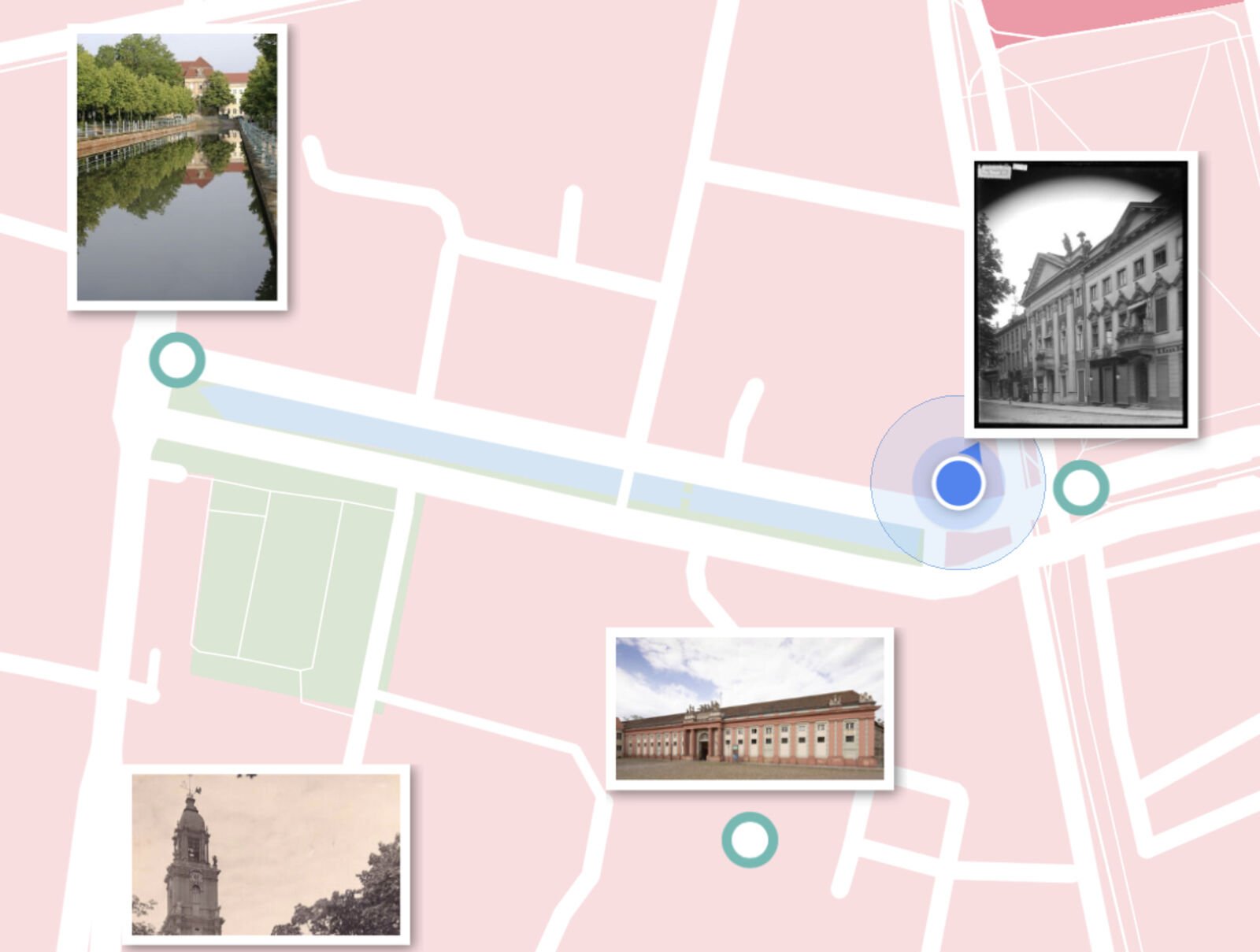

An exhibition of the Museum Barberini, Potsdam, in cooperation with the Kunstmuseum Den Haag. Under the patronage of the Ambassador of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Germany, His Excellency Ronald van Roeden.

Theme year „Holland in Potsdam“

Exhibition, event program, blog and audio walk: The Dutch Quarter in Potsdam is world famous - but the Dutch influences in Potsdam go far beyond that. From April to September 2023, the project "Holland in Potsdam" will focus on Potsdam's various connections to the Netherlands: from the Tulip Festival to migration, from visual arts to horticulture. Around 50 Potsdam cultural institutions celebrate Dutch art and influences in Potsdam in 2023 in the theme year "Holland in Potsdam". The event kicks off on April 27, Koningsdag, the Dutch national holiday and also the launch date of the blog that accompanies the cultural summer

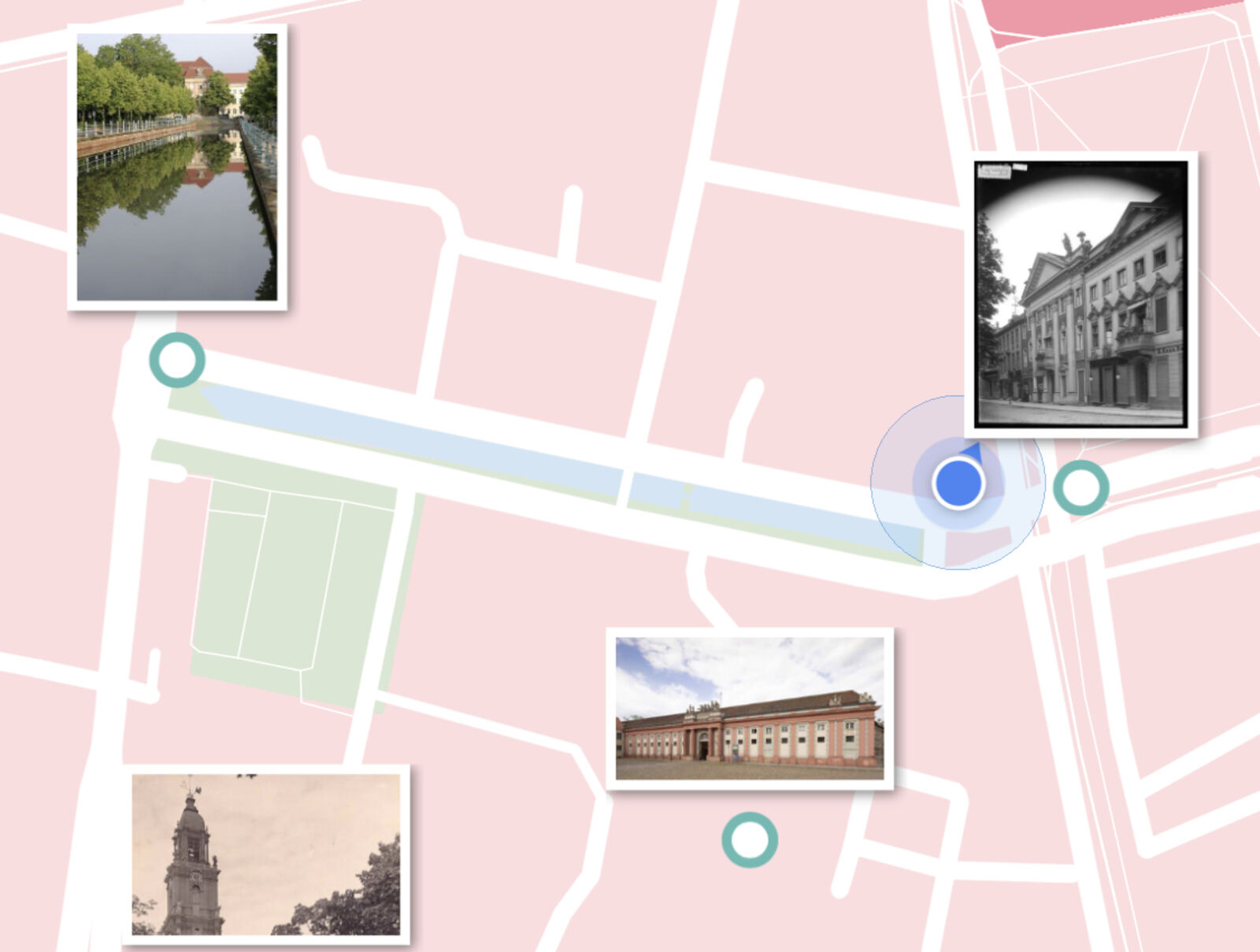

Screenshot Stadtspaziergang „Holland in Potsdam“

The multifaceted nature of the program is due to the more than 20 participating institutions with more than 50 actors from Potsdam's cultural life, including the Museum Barberini and the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation as initiators of the campaign, as well as the Potsdam Museum, the Jan Bouman Haus, the Lindenstraße Memorial Foundation, the Film Museum, the Mühlenvereinigung Berlin-Brandenburg, the Förderverein Jagdschloss Stern and the Liebermann Villa on Wannsee. They all participate with contributions to the blog, which accompanies the event program and on which articles, videos and picture series will be published every week until the fall, alternating contemporary and historical topics.

The free Barberini App offers a city tour as an audio tour to 20 different locations in the city with exciting Holland references. Like its predecessor projects "Italy in Potsdam" and "France in Potsdam," the city tour will be permanently available as an audio guide tour on the app and will also be published later this year as a small art guide in the series of publications of the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation.

All information, contributions and events can be found on the blog.

View of the exhibition

Media Partners

ARTE

Tagesspiegel

Potsdamer Neueste Nachrichten

Exberliner

rbb Kultur

tip Berlin

Yorck Kino